Sunday, June 29, 2014

Saturday, June 28, 2014

More trendy embroidery

So what's with embroidery and music videos? Last week I linked to a video that was made by machine-embroidering every cel of a long amination sequence. This week I discovered another video made with the spools and tools that you have in your studio. This one is even better -- you won't just marvel that it was all done on an embroidery machine, you'll love every second of watching your favorite stuff dancing.

Take 1,000 spools of Isacord and start building!

Friday, June 27, 2014

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Thank you!

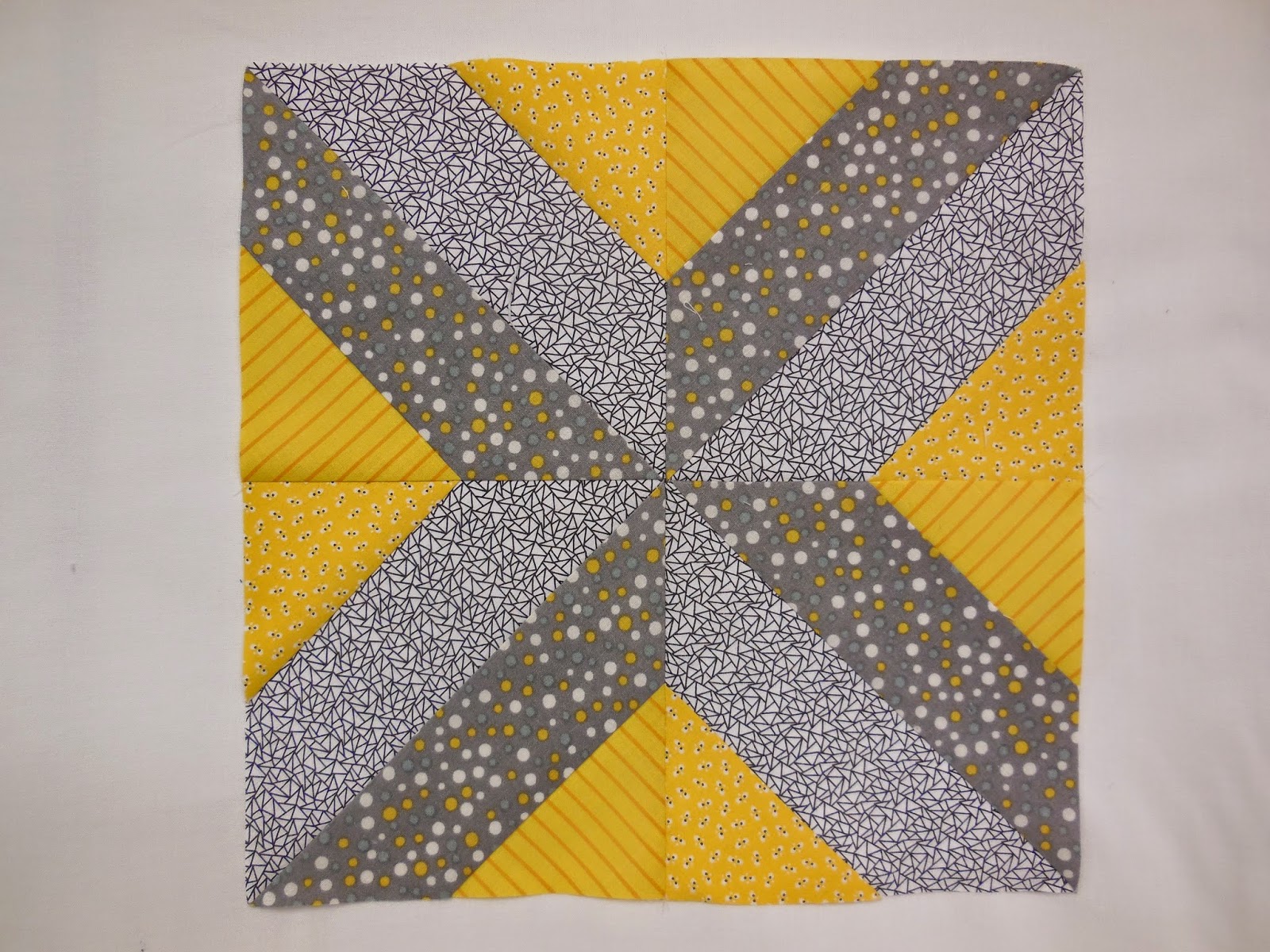

The block in question that I asked about yesterday is King's Cross or King's X.

And I sewed one up to show you (and my readers) what it looks like.

Thanks to everybody who responded!

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

I need your help!!

Yes, the book that I have been toiling over for much of my adult life is slouching toward Bethlehem, ready to be born.

But I need your help.

I am sure there is a traditional quilt block that resembles this layout, but I can't attach a name to it. Can you identify a block that looks either just like this or something sorta like this?

My eternal gratitude will follow.

(And by the way, the real book will have much better line drawings than this, thanks to a real graphic artist, not me and my drawing tools in Word.)

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Dorothy Caldwell Extravaganza 4

I wrote earlier this week about how Dorothy Caldwell's art practice is to collect artifacts, both natural and manmade, as part of her endeavors to understand a new place. I was delighted to observe how she continues this practice even if she's not in an exotic place, but somewhere as unspecial as Louisville.

On a day off between workshops we walked over the new pedestrian bridge that spans the Ohio River. When we got to the Indiana side, Dorothy pulled a plastic bag out of her purse and proceeded to collect stuff to memorialize this place. She found some mud to daub on a card, writing the date and place on the back, and then dunked some silk into muddy water to dye it. She repeated the process on the Kentucky side (even though to my eye mud on one side of the river is fairly indistinguishable from mud on the other).

On the Kentucky side we found some deep footprints in the sand at the edge of the river, partially filled with water that had seeped in. Dorothy looked around, found a root, and used it to stir up the water into an opaque dye-like solution to color her cards and silk.

Here's the root, the silk, and the card, out to dry in the sun (and the footprint/dye pot). She took the root home too as a souvenir.

By the end of the week she had assembled a "museum" in her room of her trip to Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana.

Monday, June 23, 2014

Dorothy Caldwell Extravaganza 3

As part of her week with us, Dorothy gave a lecture focusing on her activities in the "outback" of two countries, Australia and Canada. These activities have culminated in a show that has just closed in Peterborough, Ontario, and will travel to two other venues in Canada.

She points out that Australia and Canada are similar nations in many ways: They're both huge countries with the great majority of the population clustered on the edges, with vast expanses of sparsely settled, ecologically fragile territory that few people ever get to see. They were both British colonies, with substantial numbers of people who were transported there as punishment. Both are rich in resources.

Dorothy has been traveling to Australia for 20 years on a variety of travel, teaching, study and artist residence programs. Recently she received a grant from the Canadian government to conduct two parallel art projects on the two continents; in both places she would go to a remote location for several weeks, getting to know it, collecting both natural and manmade artifacts, and dyeing paper and fabric with indigenous plant and earth materials. Then she made a new set of works reflecting her experiences.

In Australia, she visited a sheep station in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia, north of Adelaide. In Canada, she went to Pangnirtung on Baffin Island, 1600 miles north of Toronto, close to Greenland.

"My work is about being in a particular place and using what's there," she said. "I want to get out into the landscape, experience the land, get to know a place by handling the materials." For instance, she hiked barefoot on the delicate tundra to get a feel for the tiny, stunted vegetation.

On both these visits she brought Japanese handmade paper, tough enough to hold up in a dye pot, and colored them with natural pigments from plants and earth. She also collected things like rusty nails and broken tools from the sheep shearers, which came home to become part of the "museum" section of her show.

"Collecting has always been an important part of what I do, since I was a little kid," Dorothy said. "My way of journaling is collecting."

After she came home from her trips, she made some of her characteristically huge fiber pieces to reflect her travels and learnings. Here's one inspired by the Arctic summer, with 24-hour daylight that often leads people to stay up all night in euphoria. Dorothy asked one of the locals how they dealt with not being able to distinguish between "day" and "night" and was both chagrined and charmed at the response: "When we're tired we go to sleep."

Dorothy Caldwell, How Do We Know It's Night, 120 x 114"

Here's a piece about the fjord on which Pangnirtung is built.

Dorothy Caldwell, Fjord, 120 x 114"

Sunday, June 22, 2014

Friday, June 20, 2014

Embroidery goes trendy

So here's my nomination for the most flamboyant use of embroidery I've seen all year.

It's a four-minute music video executed entirely as machine-embroidered animation cels, stitched onto black denim.

Read all about it and watch the video here.

Thursday, June 19, 2014

Dorothy Caldwell Extravaganza 2

The first Dorothy Caldwell workshop last week was called "Human Marks," in which we explored many ways of putting marks down. We started with paper and india ink.

Here are our brush marks, put up on the wall together to make a "quilt" of marks.

Then we attached our brushes to long sticks to make the lines less controlled and predictable. We experimented with pale ink washes and wet-into-wet. There was a stiff breeze as we worked so some of the papers went skittering across the parking lot; a dish of ink overturned onto one of the paintings; mostly we liked the accidental effects.

Here are the finished papers on display.

We cut and folded the papers into stand-up accordion books.

Here's the best part -- when I took my book out of my bag at home to show my husband, I realized that it had a little red mark on its front cover. I didn't put it there, and in fact I can't recall anybody in the room who was even using red. But it's perfect! Gives the book a very oriental flair, don't you think?

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Monday, June 16, 2014

Dorothy Caldwell Extravaganza 1

My local fiber and textile art group tries to have an internationally famous teacher come in for workshops every couple of years, and this year we were fortunate to have Dorothy Caldwell with us for a week. She taught two different workshops and gave a lecture, leaving us all in awe of her beautiful art and energized with lots of new ideas for our own work.

It's going to take me a few days to decompress and digest everything she told us, but to whet your appetite for posts to come, I'll tell you about a tiny skill she taught us, which made me so happy.

It's making string, a skill Dorothy learned from India Flint, who in turn learned it from the aboriginal women in Australia. They would make their string from plant fibers, mostly thin strips cut from pandanus leaves. Dorothy likes to use silk or organdy.

Cut or tear your fiber of choice into strips about a quarter-inch wide. Hold two strips together in your left hand (if you're a rightie) with a half-inch or so clasped between your thumb and finger, and the length of the strips extending off toward your right hand.

Grab one of the strips with your right hand and twist it away from you by rolling it between thumb and forefinger. (Thumb moves up from the tip of your forefinger to about the first knuckle, as seen in the photo.) Let's call this the twisted strip.

Now grab the other strip -- let's call it the bottom strip -- between the second and ring fingers of your right hand and hold it taut.

Wrap the twisted strip down in front of the bottom strip so it makes a neat little roll tight up against your left thumb. Grab it between the second and ring fingers, or let go if you're having a hard time hanging onto two strips at once. Now this will be your bottom strip, and the formerly bottom strip will be ready to roll between thumb and forefinger.

Get into a rhythm -- twist, wrap down in front, switch your grip, twist, wrap down in front, switch your grip. Continue till you have made a nice long string. When you get to the end of the strip, you can hold a new strip down overlapping the old one and twist them together, either tucking the ends neatly inside your roll or letting them stick out from the string like little flags.

So each strip is separately twisted away from you, but the two strips together are wrapped/twisted toward you. The opposition of the two twists is what holds the string together. You could achieve the same thing by twisting a string a bazillion times with an eggbeater, then grabbing it at the midpoint and letting it twist back on itself, but this method requires no tools and can be done as you watch TV, ride in the car, listen to a lecture or wait for paint to dry.

If you wet the strips before you twist and wrap, the string will be much neater and tighter.

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Friday, June 13, 2014

Bad ideas in fiber art for Friday the 13th

I didn't buy this yarn; I acquired it in the grab bag from my fiber and textile art group. I am grabbing and using just about any kind of yarn there is for a conceptual art project that is probably going to keep me busy for years -- way too big to make with purchased yarn. So beggars can't be choosers.

But I have to say, scented yarn is the pits. Although the fragrance at first whiff smells kind of nice, whiffing it continually as I crochet is enough to make me sick. Even when I go in another room, my hands smell of the stuff.

I can't figure out who the target demographic is, or why they would like this product. Maybe if you live upstairs from a rendering plant, this would help mask the ambient odor, but otherwise it's hard to understand the rationale. If I want my work area to smell nice I'll pick some flowers or maybe cook up a pork chop.

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

Quiltmaking 101 -- trimming your quilt

First, a word about square corners. Traditionally, quilts have them, or are supposed to have them. We think of quilts as rectangles, which makes sense with functional pieces, because beds are rectangular, and rectangular quilts will cover them and hang parallel to the floor. But even on a bed, a slightly non-rectangular quilt will not cause the world to end. A close look at any antique quilt will prove that our sainted foremothers didn't always get the corners perfect (no wonder when you think of the tools they had), but the quilts are just as precious.

When a quilt is intended for the wall, there's even less reason why the corners have to be perfectly square. Square corners aren't bad, they're just optional. In most cases you will want your corners to be square, and that's fine. But if they end up a little off, either inadvertently or deliberately, that's OK.

How you trim a quilt depends on your equipment, specifically how many cutting mats you own, and whether they can be fit together in an expanse larger than your quilt.

If your plastic ruler isn't long enough to cut the entire quilt, use a yardstick. I own a 72-inch metal ruler that is good for trimming very large quilts. A friend of mine splurged and bought four 72-inch rulers! She can lay all four onto the quilt to establish the four edges, and look carefully before she cuts anything, just as you might decide where to crop a photo by placing strips of paper over the edges.

Helpful hint: Long rulers can slip while you're cutting. If you don't have a helper to hold the other end of the ruler, and if your cutting surface has an overhanging edge, maybe you can use a clamp.

If your quilt is small enough to fit on your cutting mat (or multiple mats pushed together), trimming is easy. Arrange it on the mat so the top edge aligns with one of the gridlines. You may want to weight down the quilt so it doesn't slip around. Put your ruler across the quilt, align it with the gridline, and slice the top edge straight across with the rotary cutter.

Without moving the quilt, shift your ruler to one of the other edges and align it with the gridlines on the mat. (Or if your quilt isn't going to be exactly square, place it wherever the edge should be.) Slice that edge straight across. Repeat with the other two edges. You may want to carefully rotate the entire cutting mat, with the quilt on it, to bring the edges closer to you.

If your quilt is larger than your mat(s), it's trickier to cut the edges. You'll have to shift the quilt in mid-edge, or perhaps weight down the bulk of the quilt and shift the mat under it. You'll have to make sure that your rotary cutter doesn't go off the edge of the mat and slice up your tabletop, your carpet or your floor. Take time to think before you cut.

Cutting is easier if your ruler is longer than the quilt. If it's not, you'll have to shift the ruler as well as the mat. It's certainly possible to trim a quilt with a short ruler and a small cutting mat, but each shift is tedious as you check your accuracy and check again before cutting. You can see why quilters very quickly tell Santa they want a larger cutting mat (or maybe two or three) and a longer ruler. Although this equipment is pricey, you'll never regret its purchase, because it changes trimming from a difficult task into a snap.

The first step is always to establish a straight line across the top of your quilt, because that's the edge people look at first when they decide whether something seems crooked. Then slice the top edge of your quilt along that line, moving the quilt or your mat if necessary.

After you've cut the top edge of your quilt, align the cut edge with the gridline of your cutting mat (in the photo, the top edge is at the right). Here two cutting mats have been pushed together to give a long surface to cut the second side. Line up your ruler with the gridline and cut.

If you have an opaque ruler, line up the bottom edge with the gridlines on the mat.

If you have a transparent ruler, you can line up any of its lines with the gridlines on the mat. Transparent rulers are helpful because you can see what's underneath, but they're usually shorter than all but the smallest quilts.

With larger quilts it may be harder to establish a square corner, because the gridlines on your cutting mat are hidden underneath the quilt. Here's what to do:

Arrange the quilt on the cutting mat so as much as possible of the side you want to cut now is over a mat. Take a large cutting square, cutting mat or piece of board -- anything you know has a right angle at the corner -- and place it on the quilt, aligning it with the cut edge. Place the corner of the square piece exactly where you want the corner of the quilt to be. Use the biggest such device that you own; the farther away from the corner you can establish your right angle, the more accurate your cutting will be.

Hold the square carefully in place while you put your ruler along the edge of the square, butting it up close to the edge of the plastic. Very carefully remove the square, without moving the ruler, and trim the quilt, moving the quilt or the mat as needed.

Now go back and trim the other side edge of the quilt the same way, starting with the top edge and establishing a square corner. Leave the bottom edge for last .

So let's say you try to make square corners, and you measure and cut carefully but you work your way around and the fourth corner isn't right. Something has slipped a bit somewhere along the way as you picked up and set down your ruler, or as you marked, or as you shifted the quilt on the cutting mat, or as you moved around and accidentally nudged the quilt out of place. So your task now is to come up with the best solution.

Usually I adjust the slant of the bottom edge of the quilt to split the difference. But that's not the only solution. You can just ignore the difference, allowing one of the corners to be not-square. Or you can exaggerate the difference, and pull one of the sides out even more so the not-square looks deliberate rather than accidental.

Sometimes your quilt has gotten misshaped in the course of being pieced and quilted, and you find yourself in a similar quandary. Maybe one corner has pulled in a good bit because you quilted it more densely, and the only way to cut the quilt perfectly square is to crop in and lose a whole lot of beautifully pieced, beautifully quilted real estate -- or even worse, lose an essential part of your design. Instead, you might want to have deliberately not-square corners so you don't have to cut off your hard-won handwork.

In any case, this is not the end of the world. Your rotary cutter is meant to cut fabrics, not your wrists.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)