Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Quilting dilemmas -- pleats on the back

Got an email recently from Jaqui Brumm, whom I met at the Crow Barn in October. She wrote: "I like stitching a grid for my quilting but I get little pleats when my quilt lines cross each other. Is there a solution to this? Is it my technique or my equipment? I have it happen so often that I just leave them in or I would never finish anything. Can you give me any advice on this?"

Jaqui, if it's any consolation, the same thing happens to me. Here's the back of an otherwise impeccably quilted piece, with a little pucker. Obviously I didn't think this was worth taking out and restitching, but it is a bit less than perfect.

Let's analyze why pleats and puckers appear on the back of machine-quilted grids. First you stitch parallel lines across your entire quilt in one direction, making a series of tunnels or tubes. Because batting has a bit of loft to it (compressed at the seams, fluffy in between) the tubes tend to stand up rather than lie perfectly flat. In effect, you have made a construction that resembles corrugated cardboard. Then you turn the quilt 90 degrees and stitch across. As your new seams cross the old corrugations, they compress the tubes and stitch them together.

In an ideal world, the top layer of the tube is exactly as wide as the bottom layer, so when you put that crossing seam in, both top and bottom layer will be perfectly flat. But if the bottom layer of the tube has somehow gotten to be a little wider than the top, you get a pleat.

How might that bottom layer get to be wider? At its simplest, imagine you're back on the first part of the grid, stitching parallel lines, each one to the right of the row before. You tug and/or smooth the unquilted part of the top layer out to the right as you stitch, keeping it nice and taut. It looks great, but maybe when you were tugging and smoothing you tugged harder on the quilt top than you did on the batting and backing. Oops! That means you will inadvertently stitch a tube that's wider on the bottom than on the top.

In theory, that's why we baste or pin the layers together before we quilt, to keep the layers even. But if your quilt is densely pieced, with lots and lots of seams, basting or pinning can actually be counterproductive. That's because it's difficult, perhaps impossible, to press a large quilt top perfectly flat, with all the seams open to their maximum. Yet as you quilt, tugging and smoothing to the right with every row of stitching, the seams open just a bit more; by the time you get to the edge of a large, densely pieced quilt, it may have stretched an extra half inch or more. (That's also why you should leave a generous margin of backing fabric around the edges of your quilt top instead of cutting the two to match.)

To prevent pleats, there are several things I do in self-defense, most of them concentrating on that first pass of the grid. If the first set of parallel stitches is done well, there shouldn't be many problems with the rows that cross it later.

I almost always use drapery-weight fabric for backings, not quilting cotton or muslin, and I never wash it first. The stiffer the backing, the more likely it will be to stay flat and where you want it; limp is your enemy.

I don't baste or pin the whole quilt. That leaves the layers loose and allows me to frequently adjust them. I will pin a midline just to hold everything together as I put in my first row of quilting stitches, and I might put in one row of pins three or four inches to the right of my stitching, but mostly I rely on frequent tugging and smoothing on the unquilted portion of the sandwich to keep everything in place.

When I tug and smooth, I often tug separately on the backing in addition to smoothing the quilt top. Because I usually roll my quilts when working with a walking foot, it's hard to grab onto the backing separately; its end is usually buried inside the roll. So I frequently take the entire quilt to my work table, quilt top up, unroll it and press again.

I start by separating the backing from the batting and top, fold the batting and top away and press the backing. Then I fold the batting back in place and press it over the backing. Finally I fold the quilt top back in place and press everything together. After I've quilted another six to ten inches, I'll press it again. That six to ten inches coincides with how much quilting I can do before having to unroll a new segment of the quilt.

I check the back of the quilt a lot, probably every third or fourth row of stitching, to make sure the backing is smooth and square. I don't want it to be loose and puffy between lines of stitching, indicating that the bottom layers of the tubes are going to be too wide, and I also don't want it to shift off grain on the bias, which might make diagonal pleats or puckers.

Once the first half of the grid is sewed right, it's a lot easier to put in the crossing stitches. I still check the back every now and then just to make sure no pleats are happening. And if all else fails, console yourself that people generally don't see the back of your quilt anyway.

Monday, December 29, 2014

Christmas weekend workshop

So it's the second day of Christmas, and you eat leftovers from your Christmas feast, police up the torn wrapping paper and ribbons, get the chairs put back where they belong and your dining room table back to its original configuration, take a walk if the weather is at all decent. Then it's the third day of Christmas and aren't you getting a little antsy to be done with it all? Aren't you getting a little tired of the Christmas carols on the radio? Isn't it time for some art?

Fortunately, my favorite local museum, The Carnegie Center for Art and History, knew we would be feeling this way and held a workshop on altered books. The leader was Ehren Reed, who works in various permutations of mixed media, especially books. And since the Carnegie Center is a branch of the Floyd County Public Library, it was easy for them to find a whole load of deaccessioned library books for us to work with.

Ehren told us our first decision had to be whether to retain the "bookness" of our book -- in other words, keep the format so you can turn the pages and see what's inside -- or use it for sculpture. Most of the others at the workshop chose bookness, but much as I love playing with text, it takes a lot of time to find poetry and I wanted a project I could finish in four hours. So I went for sculpture.

At first I didn't know what I wanted to do, so I proceeded to cut my book apart. When I got the pages detached from the spine and covers, I realized that the back was gorgeous, sewed in different colors of thread and stained from some mysterious event in its past. I cut the pages away so the back was only about 1/2 inch tall.

That was nice, so I deconstructed two more books, found their backs to be equally interesting, then made this composition using one of the covers as a support.

Best of all, I now have hundreds of loose book pages that I can use in subsequent art projects. Lots of poetry to be found there, or perhaps lots of support for collages. Or who knows what else.

Altogether, an excellent way to spend the third day of Christmas.

Sunday, December 28, 2014

Thursday, December 25, 2014

Deck the trees

All the Christmas ornaments have been delivered so now I can show you what I made this year. I've been doing a lot of hand stitching in recent months, especially of text, and it seemed like a good idea to embroider people's names on their ornaments. This is the third year in a row that I've done full names, but don't get too complacent, people, we may go back to initials next year.

I found an old linen tablecloth that made a great substrate for embroidery, and had a bunch of green wool felt scraps still sitting on my worktable after I trimmed the edges of my Quilt National piece.

Here are a bunch of the completed ornaments. Don't you think the circle and oval are particularly elegant? After a year of daily stitching in 2012 I did get pretty good at making curves loop around and meet up smoothly at the starting point.

Here's Kate ready to put hers on the tree.

Merry Christmas!

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Monday, December 22, 2014

Number one in the series

So a couple of months ago I attended a workshop where we were doing stitched shibori, the kind where you have to draw up the stitched fabric tightly, tie off the threads, and cut off all the long ends. Found myself with a whole pile of cut ends on my table, and during a slightly boring presentation started tying them into knots. Just plain old overhand knots, but if you kept tying knots upon knots they developed an interesting knobby texture that seemed intriguing.

I tied all my loose cut ends into the little pieces that were developing shape and substance, and then cut some new threads to tie in, longer ones so I could knot farther without leaving so many cut ends hanging out. The following day, after we had dyed our shibori in indigo, I took out the stitching and knotted those threads, now a beautiful blue, into my little pieces.

The thread is plain old Coats and Clark upholstery thread, nice and strong, somewhat fatter than sewing thread, with a slight sheen. After I used up all the bits left over from shibori, I bought a second color of thread and continued to knot.

For several weeks I've been making these little doodads and piling them on my work table, not sure of exactly how I wanted to finish and display them. When something is only an inch or two long, you have to give some thought to display; you can't just plop it down on a pedestal and call it sculpture. But just in time for Christmas, I figured out the answer -- at least, I figured out one answer, enough to get the first piece on its way to my friend.

I'll tell you more about the process and show you more pieces as I get them finished, but here's number one in the series. I'm calling them "Specimens."

The frame has a 2x3-inch opening, and the specimen is about 1 1/4 inches tall. It has a lot of knots in it.

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Friday, December 19, 2014

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Gift exchange -- art!

I wrote earlier about the gift exchange at my fiber art group's annual holiday party and showed you several of the functional pieces that were made and given. Today, some that were not functional at all, unless you happen to think that art is necessary, like breathing.

a collage/assemblage by Alyce McDonald

a quilt, wraparound-mounted on a canvas by Marti Plager

Spanish-marbled paper by Debbie Shannon

a needlefelted piece by Kathy Loomis

Monday, December 15, 2014

Gift exchange -- stuff you can use

My local fiber and textile art group has an annual holiday party in December, with a gift exchange as the highlight of the evening. When I first joined the group more than a decade ago, the rules were to spend about $5 on a gift, supposedly fiber-related in some way, and the gifts were predictably minimal. The worst one I remember was a package of rubber shapes to glue onto your bathtub to minimize slipping -- "fiber-related" because they were called "shower appliques." Appliques, get it?

After a few years I joined the board and one of my early suggestions was that since we were all allegedly fiber artists, we should all be able to come up with a handmade gift for the party. To my surprise, my snarky observation was endorsed by everybody else and we changed the rules. Now you must make a gift, one that would sell in the vicinity of $20-25 retail.

And the holiday party has become a lot more fun! Last week was perhaps the best one I can recall, with a huge variety of gifts. Here are some of the functional ones:

Bags:

Scarves:

Jewelry:

Books and notecards:

Even bowls:

Now don't you wish you were at this party?

Now don't you wish you were at this party?Sunday, December 14, 2014

Friday, December 12, 2014

Sign of the week

PS Two minutes later, the train had come to a halt, stretching out of sight in both directions. Here's what happened then:

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Shallow alert

In the trashy weekend tabloid that appears in our Sunday newspaper, we read that an actress I've never heard of, starring in a miniseries about the four Biblical wives of Jacob, has "a newly acquired skill," thanks to filming the movie.

"I had to learn how to separate the wool that came straight from the sheep, clean it and put it on spools," she proudly tells the interviewer. (I guess her immersion in useful fiber processes didn't extend to learning the actual terms for these newly acquired skills.)

She didn't think as much about the dust on location. "We were covered the entire time we were filming," she complained.

Here she (the one at left in blue) and her girlfriends pretend to be carding and spinning. I'm no ancient history scholar but it strikes me that the clothes seem to come from considerably later times (check those gathered, set-in sleeves and that plunging neckline on the chick in pink.) Likewise, I'm no scholar of textile history but that carding setup also looks suspiciously modern. And did they have lathes in Biblical times to turn those spindles?

And where's all that dust she was bitching about?

I am so sorry that I missed the miniseries, which ran earlier this week.

Wednesday, December 10, 2014

My new "day job" 3

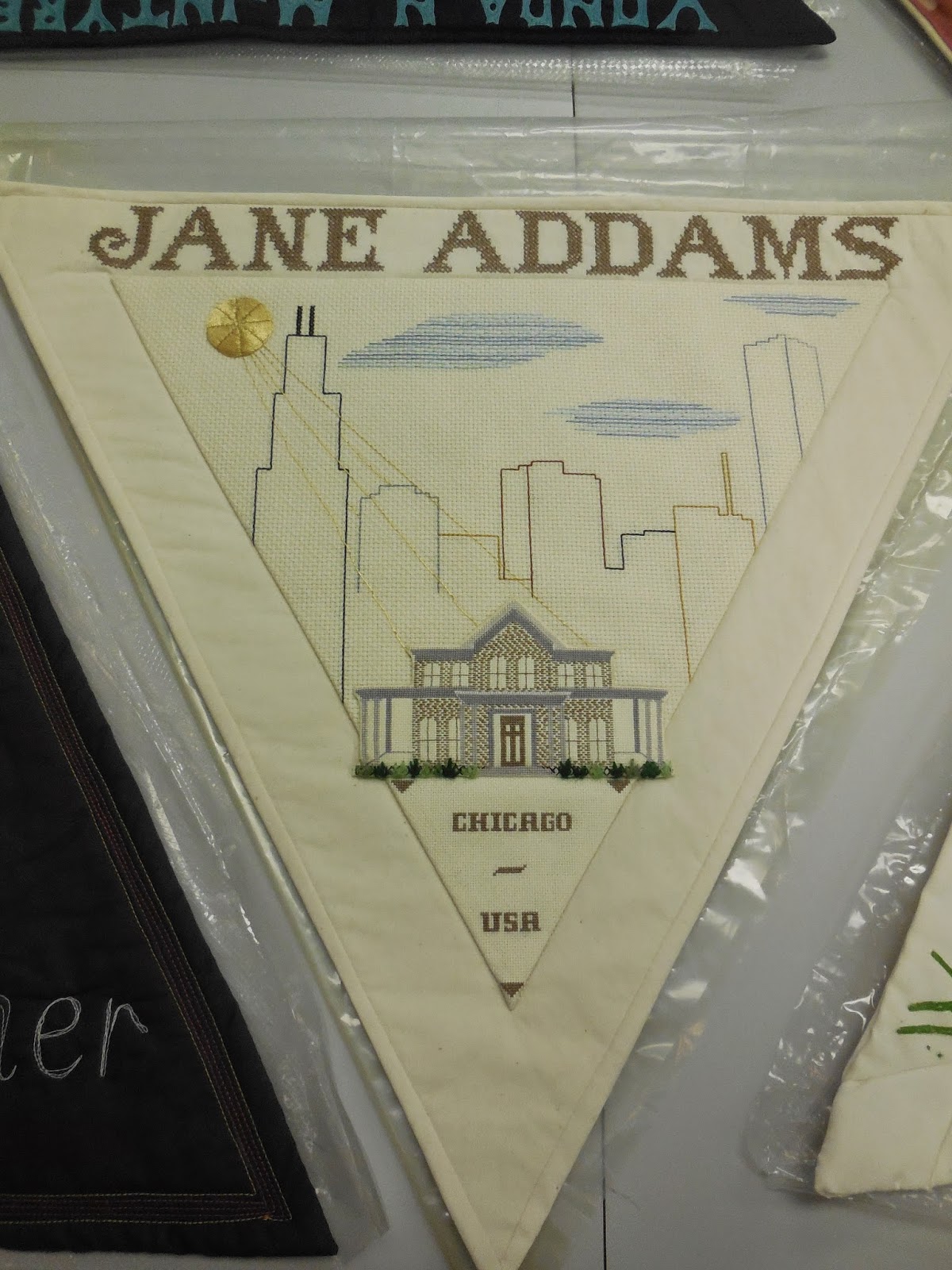

The 600+ panels in the International Honor Quilt collection were supposedly catalogued in 1994, but don't try to take that to the bank. The database is supposed to include information on the panel, the woman or group honored in the panel, the maker of the panel and biographical information about her, the maker's statement (about why she chose the honoree, how she made the panel, or whatever else she wanted to say), technical information on the panel's condition, measurements, materials and techniques, and a detailed description of the panel.

Materials, techniques and description are my responsibility, while the other fields are being checked and corrected by others on the project staff. In my three fields, we're finding that some panels have no information at all, while others have been incorrectly described.

For instance, 18 of the first 54 we've gone through had no information on materials, techniques and description! That's a lot of blank spaces in the data base.

But even the ones that have been filled in by past cataloguers need to be carefully checked for accuracy. The previous cataloguers sometimes confuse hand and machine stitching and use catchall terms such as "hand sewn" instead of distinguishing between hand piecing, hand applique and hand embroidery. Considering that this project is officially about "quilts," it's discouraging that they have not carefully distinguished between quilting and other forms of stitching.

One of the cataloguers seemed enamored of the term "partial machine construction," which means nothing to me. "Top stitching" is frequently used as a descriptor, except sometimes it means machine applique, other times it means quilting, still other times it means embroidery.

the cataloguer thought this beautiful padded satin stitch was machine embroidered

The previous cataloguers also didn't pay much attention to how the edges of the panels were finished -- traditional quilt binding, facing, knife-edge finish, fabric from the front or back of the panel folded over the edge and stitched down on the other side, or whatever. In many cases there was no description at all of the edge, and in others it wasn't accurate.

In addition, we've decided that consistency in the descriptions is a virtue, so I'm rewriting them to always begin with the "border," which almost always contains the name and location of the honoree, then describe the interior triangle, then the edge finish, finally the reverse.

So I inspect each panel, compare it to what the cataloguer wrote, poke and prod the work to determine what techniques were used, occasionally feel the goods with my ungloved hand to identify the material, and write my own notes. Then at home I type it all into the database; it usually takes me a bit longer to type up the notes than it did to inspect the panels.

The curators had acquired several pairs of those baggy, limp white cotton gloves to protect the quilts, but I said we needed Machingers to make it easier to work, so as of yesterday we're the proud owners of four pairs! I have a long embroidery needle that I use to poke at the work and lift an edge or pull a seam open to see how it was stitched, a ruler to measure the borders and a magnifying loupe to get a better look at the stitches if necessary. And we had to get a metric tape measure to do all the dimensions in centimeters (we argued for quite a while about whether to stick with inches, but couldn't agree on whether to say 1.125 or 1 1/8 and whether those three decimal places were misleadingly "accurate").

I had to gingerly poke at this one to determine that the tiny orange stitches are made with a punch needle, not french knots

But enough about research methods; more in subsequent posts about what I'm finding as I inspect the panels.

Labels:

feminism,

fiber art,

International Honor Quilt

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

My new "day job" 2

When I learned last summer that the University of Louisville School of Art had acquired the panels made by hundreds of volunteers to accompany Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party, my heart sank. I had two major concerns.

First, I was afraid that the panels would be portrayed as works of art, even though I suspected that many of them would have that loving-hands-at-home air -- exhibiting neither excellent craft nor compelling visual imagery -- that is the antithesis of serious fiber art. I was afraid that such an endorsement would taint the air, at least locally, and make it easier for people to lump all fiber art into the same shallow bucket, awash in earnest sentimentality.

Second, I was annoyed that the collection was officially named the International Honor Quilt, even though many of the pieces in my first viewing were not quilts. It's the same quarrel I have with the "AIDS Quilt;" it chops me that the "most famous quilt in the world" is not a quilt, because that disrespects the many works that truly are quilts and encourages people to be haphazard in how they talk about all fiber art and textile techniques. (Chicago was also involved in the genesis of the AIDS Quilt, so perhaps her cavalier attitude toward nomenclature affected both projects.)

not a quilt

When my fiber and textile art group met with the curators in August and got to see some of the panels, I raised this issue of nomenclature. It didn't get much response from the curators, none of whom had much experience with fiber art, until I said, "I know that you must be really annoyed when people refer to your work incorrectly, using the terms 'painting' and 'print' interchangeably." (Winces from the other side of the table; laughter from the assembly.) "Well, that's the same way I feel when people don't use the term 'quilt' correctly -- it's like fingernails on the blackboard."

But I left the meeting with a feeling that the best -- perhaps the only -- way to be sure my concerns didn't become unpleasant realities was to get involved myself. I was reassured that the curators had backed away from the earliest PR-release language touting the collection as "an artistic treasure" and were viewing it more as a sociological event, a remarkable outpouring of response from women around the world, embodying the ardent feminism that today seems quaint.

not a quilt

And I was determined to honor the work of these women by describing it correctly. The curators said at the meeting that they hoped to get volunteer help from our textile group in the cataloguing, and I immodestly thought that I probably had as wide a knowledge of textile techniques as anybody else in the group. So I told the professor in charge of the project to count me in.

Labels:

feminism,

fiber art,

International Honor Quilt,

quilts

Monday, December 8, 2014

My new "day job" 1

I'm about to tell you several posts worth about my new volunteer project at the School of Art at the University of Louisville. Today, the back story.

It starts with Judy Chicago's magnum opus, The Dinner Party, made in 1975-6, first exhibited in 1979 and now on permanent display at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Widely regarded as one of the high points in feminist art, it is a huge three-sided table with 39 place settings, each one commemorating a famous woman in history with an individualized plate and placemat. An additional 999 women were memorialized on floormats on which the table rested.

The exhibit toured the world for nine years, drawing huge crowds, and many of the women who saw it were moved to wish that their own favorite women could be included in the show. At some point Chicago invited submissions from anybody who wanted to make a panel. Hundreds of panels came in, and on later stops in the tour they were displayed as part of the Dinner Party installation.

The panels covered famous and not-famous women; many people honored their mothers, grandmothers, next-door neighbors and teachers. Others chose women's organizations such as the League of Women Voters, the American Association of University Women or La Leche League. Some depicted fictional, mythological or Biblical characters, groups such as farm women or pioneers, or universal themes such as menstruation.

There were only two rules: each panel should be an equilateral triangle, 24 inches on a side, and around the edges of the triangle should be written the name of the honoree and her city and country. Beyond that, the format, materials and techniques were up to the makers.

After the world tour, both The Dinner Party itself and the more than 600 volunteer-made panels went into storage. Last year, Chicago's foundation donated the panels to the University of Louisville, and the school is now grappling with the task of properly documenting them.

In a moment of some kind of mental aberration, I decided that I needed to be involved with this project, so I'm spending several hours a week with the panels and a spreadsheet, helping the curators with the technical details of textile techniques and materials. I'll tell you more about the project and my role in it in subsequent posts.

Labels:

feminism,

fiber art,

International Honor Quilt

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)